This scientific study is presented in full with permission from Dr. Kamarul Zaman Ahmad

The Relative Effectiveness Of Techniques In Hypnosis, Time Line Therapy®, Neuro Linguistic Programming (NLP) In Reducing Stress And Negative Emotions

By Dr. Kamarul Zaman Ahmad

Senior Lecturer

Faculty of Business & Accountancy

University of Malaya

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

ABSTRACT

The effectiveness of hypnosis to combat stress has been well documented. However, there has been no reported research that compared the relative effectiveness of hypnosis with dissociative techniques in Neuro Linguistic Programming (NLP) and another technique known as Time Line Therapy®. This experimental research involved 32 test subjects and 32 control group subjects. Results of T-Tests revealed that with the test group, there were significant reductions in stress levels after undergoing the procedures compared with before. As expected, there were no significant changes in the control group.

INTRODUCTION

The benefits and effectiveness of hypnosis has been well documented and reported in peer reviewed journals such as the International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, the American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis and the Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. Sadly however, there appears to be no reported research that compared hypnosis with other techniques such as Neuro Linguistic Programming (NLP) and Time Line Therapy® (referred to below as “TLT”). On closer inspection one particular technique in NLP usually referred to as the “dissociative technique”, has remarkable similarities with hypnosis. Similarly, TLT requires the subject to go into a hypnotic trance as part of the process. TLT is however a much more structured process than the dissociative technique in NLP and hypnosis. The creators of TLT (James and Woodsmall, 1988) require the therapist to read verbatim from a script. Furthermore, one must be certified in TLT by either one of them before being regarded as sufficiently qualified and authorised to conduct the procedure (James and Woodsmall, 1988).

Thus, it would be interesting to compare the outcomes of a very structured process i.e. TLT, with a lesser structured process i.e. NLP, and a relatively unstructured process of progressive muscle relaxation and mental imagery techniques in hypnosis.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Greenberg and Baron (2000) define stress as “a complex pattern of emotional states, physiological reactions and related thoughts in response to external demands.” Examples of such demands are demands of work assignments and interpersonal relations between co-workers, spouse and children. Strain is the accumulated effects of stress expressed as deviations from normal patterns of behaviour or activity i.e. a consequence to prolonged exposure to stressful events (Greenberg and Baron 2000).

Stress is a factor of modern day life. Stress is the second most frequently reported work-related health problem across Europe, according to the Third European Survey on Working Conditions (Paoli and Merllie, 2001). This is because of longer working hours, frequent changes in culture and structure as well as the loss of lifetime career paths (Cooper and Locke, 2000). Much has been written about the dangers of stress. Apart from loss of health, the mistakes or wrong decisions which employees make under the effect of stress can cost even more than their loss of health (Treven & Potocan 2005). Gilboa, Shirom, Fried & Cooper (2008) found in a meta-analytic study involving 35,265 employees that there are seven work-related stressors: role ambiguity, role conflict, role overload, job insecurity, work-family conflict, environmental uncertainty and situational constraints. All these stressors had a negative correlation with performance at work. In particular, role ambiguity and situational constraints had the greatest negative correlation with performance.

While previous studies in management such as the above focused on the causes of stress, they failed to look at the effectiveness of hypnosis in reducing stress. Much has been written about the effectiveness of hypnosis in medical and hypnosis journals. For example, hypnosis has been shown to reduce blood pressure and mild hypertension (Gay, 2007), improve the immune system of the body (Neuman, 2005; Kiecolt-Glaser, Marucha, Atkinson and Glaser, 2001; Gruzelier, Smith, Nagy and Henderson, 2001) and even to promote hair growth in those with alopecia areata i.e. a type of baldness (Willemsen and Vanderlinden, 2008). Elkins, Jensen and Patterson (2007) reviewed thirteen studies that investigated the use of hypnosis for the treatment of chronic pain and found that hypnosis interventions consistently produce significant decreases in pain. In an experiment that involved having normal subjects submerge their hands in hot, circulating water, brain scans showed that the pain signals changed dramatically depending on what type of hypnotic suggestion they were given – even though the stimulus stayed the same (Manzer 2003). “When your’re using hypnosis to reduce pain, you’re actually acting on networks of brain areas that are involved in the experience of pain.” Smith (2003). An array of mind-body therapies (e.g. imagery, hypnosis and relaxation) when employed pre-surgically can improve recovery time and reduce pain following surgical procedures (Astin, 2004). “We have a lot more control over our pain than most of us realize” (Manzer 2003). Pain systems in the brain are bi-directional and can shut off pain reports as well as receive them. (Smith 2003). Hypnosis has also been used to manage anxiety and pain associated with colonoscopy for colorectal-cancer screening among six patients (Elkins, White, Patel, Marcus, Perfect and Montgomery, 2006). It was found that fifty women who elected to participate in hypnosis prior to childbirth took significantly less sedatives and anaesthesia during labour compared to the fifty-one women in the control group (VandeVusse, Irland, Berner, Fuller and Adams 2007). Hypnosis has also been shown to be effective in reducing stress among those with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Keefer and Keshavarzian, 2007). It has also been shown to be effective in reducing pain and trauma among burn patients (Shakibaei, F., Harandi, A.A., Gholamrezaei, A, Samoei, R. and Salehi, P., 2008), reducing chronic pain in persons with disabilities (Jensen et al 2008) and suppressing emotional responsivity (i.e. emotional numbing) during recall of the distressing memory (Bryant and Fearns, 2007).

Hypnosis has been shown to be effective in combating stress and its related symptoms. For example, in a meta-analytic review as early as 1980s it was found that for migraine headaches and tension headaches, relaxation training was significantly more effective than medication placebo (Blanchard, Andrasik, Ahles, 1980). 25 out of 25 children (mean age 15) reported a decrease in headache frequency and/or intensity following the use of hypnosis (Anbar and Zoughbi, 2008). Hypnosis has been confirmed to be just as effective in more recent times. Hammond, D.C. (2007) found that it is effective in the treatment of headaches and migraines, concluding that it meets the clinical psychology research criteria for being a well-established and efficacious treatment and is virtually free of the side effects, risks and adverse reactions and ongoing expense associated with medication treatment. Hypnosis has also been used in the treatment of chronic combat-related post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Abramowitz, Barak, Ben-Avi, and Knobler (2008). Hypnosis has been shown to be effective in the treatment of a woman with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) resulting from her experience of having large glass doors collapse and shatter on top of her at work on two separate occasions (Carter, 2005).

Hypnosis has also been shown to be an effective therapeutic method when used along with other procedures. For instance, Kirsch, Guy and Guy (1995) performed a meta-analysis of 18 studies that indicated that patients who received cognitive behavioural therapy along with hypnosis for pain control, weight loss, insomnia, anxiety and high-blood pressure improved on average, 70% more than did patients who received cognitive behavioural therapy alone. Cognitive hypnosis has been shown to reduce depression in 84 volunteers more effectively than cognitive behaviour therapy (Alladin and Alibhai, 2007).

Thus, there is abundant evidence on the value of hypnosis. However, there no reported studies of the effectiveness of another technique called Time Line Therapy® (TLT) developed by James and Woodsmall (1988) even though it is taught to thousands of people all over the world. TLT is a specific process that also involves the use of trance and the purpose is to remove all negative emotions from all the memories from the past. In a way, TLT can be viewed as a form of hypnosis in that it requires the therapist to put the subjects in a trance state while the intervention work is done. However, Dr. Tad James, in his seminars, has repeatedly emphasised that TLT is a subject in its own right. One of the reasons is that TLT requires the therapist to take the subject through a specific series of steps. Furthermore, what makes TLT different from hypnosis is that TLT procedures require the therapist to read verbatim from a prescribed script and not deviate from it. In fact Dr. Tad James has successfully obtained and registered a Trademark and regularly enforces it. Furthermore, anyone wishing to use this technique must first of all have obtained certification in TLT (at least at the Practitioner level, if not at the Master Practitioner or Trainer level) before he/she is authorised to conduct TLT with others. As mentioned earlier, the TLT process requires the Practitioner/ Trainer to read from a script and adhere to it strictly.

The purpose of TLT is to systematically remove all major negative emotions attached to all memories from the past. It does not remove the memories themselves, just the emotions that are attached to them. It also does not prevent the subject from feeling those emotions in the future, for it is not the purpose of TLT to turn people into zombies. The first two negative emotions that are attended to are usually anger and sadness. Anger is the first because it is a stimulant that often causes harm to others. Sadness is next because it is a depressant as well as an emotion that causes harm to self (James and Woodsmall, 1988). The process of TLT is trademarked and the author is not authorised to reproduce the script or describe the procedure in detail here. Briefly speaking, TLT requires the subjects to first of all elicit the location and orientation of their time line, float above it, and remove all the negative emotions attached to all memories from the past, starting from the first experience the subject felt that emotion. The entire process, on average, takes less than fifteen minutes. Having said that, there is a whole lot more to the technique and requires someone certified in TLT, before he or she is permitted to perform the procedure on others.

Another technique examined in this research is the dissociative technique of Neuro Linguistic Programming (NLP). NLP is a way of organising and understanding the structure of subjective experience and is concerned with the ways in which people process information but not necessarily with the specific content of that information (Einspruch and Forman, 1985). NLP evolved from a study of neurology, linguistics, and patterns or programmes of behaviour (Thomson, Courtney and Dickson, 2002). Developed in 1975 by Richard Bandler, a mathematician and John Grinder, a linguist, NLP has been clinically demonstrated as a powerful technology for engendering change (Bandler and Grinder, 1979; Grinder and Bandler, 1981). Bandler and Grinder developed skills of modelling that allow one person to identify in a specific sequence of thoughts and behaviour in one person and teach that structure to another person (Dilts, Grinder, Bandler, Cameron-Bandler and DeLozier, 1980). Using this, Bandler and Grinder were able to ferret out essential patterns used by Milton Erickson, Virginia Satir, Fritz Perls, and teach them to others. NLP is therefore often described as a “study of human excellence” and “the difference that makes a difference” (Andreas and Faulkner, 1994). According to Bandler and Grinder (1979), NLP can be used to cure phobias and other unpleasant feeling and/or responses in less than an hour. However, Sharpley (1984) reports that the amount of published data supporting NLP as a viable model for therapeutic change is minimal. This is true until today. Nevertheless, many skilled NLP trainers have a wealth of clinical data indicating that this model is highly effective. “Clearly these practitioners would provide a service to the field by presenting their data in the literature so they may be critically evaluated” Einspruch and Forman (1985).

One of the objectives of the research is also to provide empirical support for Einspruch & Forman (1985). There have been many previous research (cited in Einspruch & Forman, 1985), that have attempted to debunk NLP. However, Einspruch & Forman (1985) defended NLP and instead, attacked previous research stating that such “failed” research used flawed methodologies – more specifically by using researchers who are not properly certified as trainers, master practitioners or even practitioners in NLP. As such, the aforementioned criticised research had experiments that resulted in the outcomes of the test groups being no different from the control groups. Einspruch & Forman (1985) revealed that all of the 39 empirical studies reviewed failed to provide adequate investigator training. For example, in Dowd and Hingst’s (1983) study, students who had no experience as therapists were trained in four 90- minute sessions (i.e. a total of 6 hours, in contrast to a Practitioner Certification course that is 130 hours!). This does not provide enough time to develop mastery of the NLP framework including the vital pre-requisite to any NLP procedure – establishing rapport. Rapport is not just about matching representational systems. It is a complex matter involving matching and mirroring many other aspects such as body posture, facial expression, breathing etc. Einspruch & Forman (1985) pointed out that many previous studies such as Appel (1983), Brockman (1980/1981), Cody (1983), Ellickson (1983), Dorn (1983), Dowd and Pety (1982), Ehrmantraut (1983), Falzett (1981), Green (1981), Hammer (1983) and Paxton (1981) did not understand that NLP requires the cooperation and submission of the respondent very much like in hypnosis. Furthermore, as Einspruch & Forman (1985) pointed out, if comparisons are to be made with other treatment approaches, the therapists using any comparative model, should be equally proficient. NLP is a complex model requiring extensive training before a practitioner may legitimately undertake a study of this nature. One cannot simply attend one or two workshops, read a book and assume that he or she can effectively perform NLP therapy any more than this can be assumed for any other model of therapy (Einspruch & Forman 1985) including hypnosis and TLT.

OBJECTIVES

Although there are some more recent research such as Ashok & Santhakumar (2002) that have showed the benefits of using NLP at work, there is no such experimental research that simultaneously investigated in a single study, the effectiveness of using hypnosis, TLT and NLP as a means of reducing stress and negative emotions. Thus, the first and main objective of this research is to find out about the relative effectiveness of selected techniques in these three fields in reducing stress and negative emotions. The results of the test groups were compared with a control group. The second objective of this study is to address the issues raised in Einspruch & Forman (1985) – namely about the lack of qualification and experience of researchers conducting experiments. The researcher in the current study is a certified trainer of hypnosis, TLT and NLPHyHY. It is worthwhile to point out that while Einspruch & Forman (1985) defended NLP, they themselves failed to conduct experiments to show the contrary. No one else has done so until today, and this justifies this research to be done. The researcher is not only a Practitioner and Master Practitioner, but also a certified trainer of hypnosis, TLT and NLP attached with the American Board of Hypnosis, the TLT Association and the American Board of NLP respectively. The researcher has over two years of related experience since graduating as a Trainer. He also holds a PhD pertaining to Psychology and has over seven years of post-doctoral experience.

METHOD

Respondents in the test group were participants of the same seminar/workshop entitled “Empower yourself Through NLP, TLT and Hypnosis” but from two separate sessions. Both sessions were identical and were conducted personally by the researcher. The participants also consented to participating in this research.

The intensity of stress and negative emotions were measured using numerical scales from one to ten – ten being the most intense and one being the total absence of such feelings. Similar scales were used for hypnosis, NLP and TLT procedures.

The session started on the morning of the first day with hypnosis. Participants were required to indicate their current stress levels (from one to ten) prior to the activity. Then, progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) techniques were taught to the participants along with mental imagery of pleasant surroundings. Participants were invited to imagine themselves floating on a cool stream in a pleasant forest and finally landing on a beautiful beach by the sea. The process was accompanied by the relevant sounds of nature played on a sound system. During this time the participants were asked to gauge their level of stress/relaxation. Then, the participants were gradually brought back to full consciousness. Immediately therafter, the participants were again asked to indicate their scores on the questionnaire – one score for how relaxed they felt during the hypnotic procedure and the other regarding how they felt after they were brought back to full consciousness.

The NLP session was conducted during the afternoon of the first day. The participants were asked to remember an unresolved event that they still felt stressed about. They were asked to remember it vividly and associate themselves into the memory i.e. see through the first person view. They were asked to indicate their level of stress when associating into the memory. Then, they were taught the dissociative technique i.e. see through the third person view. Then, they were asked to change the “submodalities” of the mental picture i.e. by changing it from colour to black and white, reduce the clarity and size and gradually push the picture further and further away from them. After that, the participants were told to record their score about how stressed they felt about the event.

The TLT session was conducted during most of the second day. During the morning, the researcher explained the theory, basis and techniques in TLT. Then, the procedures were done during the afternoon as follows: participants were required to first of all recall one event in which they felt the most anger which was responsible for them feeling stressed. They were asked to record the level of the emotional intensity of anger. Subsequently participants were taught the process of TLT and a group induction was performed on them to release the anger on all events from the past including the most significant event. Respondents were then asked to record the level of emotional intensity of anger after the TLT process. The same was repeated for the negative emotion of sadness which was also responsible for them feeling stressed.

The control group comprised of part-time Master of Business Administration students at a University who were all working people and of roughly the same age group and job level as the test groups. Coincidentally, the test groups also had some students from the same course at the same university. Thus, in terms of demographics, they are similar. Respondents in the control group recorded their stress levels and intensity of negative emotions once, then a second time twenty minutes later. They were not taught any of the techniques aforesaid.

RESULTS

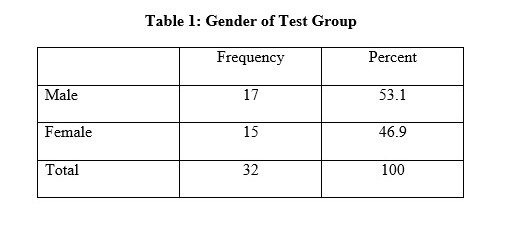

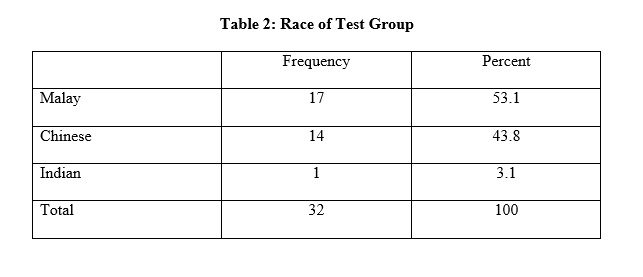

The mean age of the participants in the test group was 38 years, i.e. ranging from 22 to 61. The age range was not so wide in the control group i.e. 28 to 47 years, but the mean age was similar to the test group. In terms of racial composition, there were 17 Malays, 14 Chinese and 1 Indian in the test groups. There were also 17 Malays, 14 Chinese and 1 Indian in the control group.

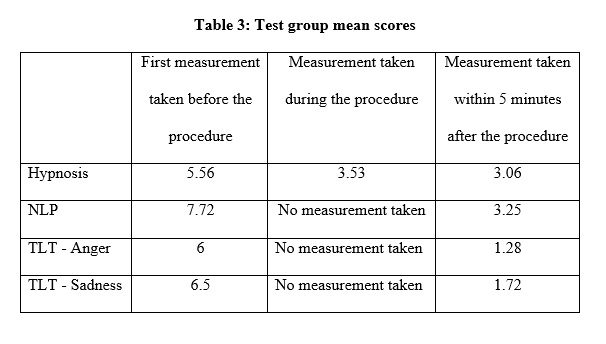

For the test groups, paired sample t-tests were performed using SPSS to assess the changes in intensity levels of emotions before and after the participating in the techniques in hypnosis, TLT and NLP. There were significant reductions in intensity levels for all three techniques. As expected no such change was recorded among the control group. The average score for the participants in the test group before being taught the hypnotic techniques was 5.56. The average score during was 3.53. T-test showed that the differences were significant at the 0.01 level. Participants reported being very relaxed during the progressive relaxation and mental imagery exercises. The average score of the participants after hypnosis was 3.06. T-tests showed that there were no significant differences in the scores during, compared with after the hypnotic induction, indicating that the relaxing effects of hypnotism continued to work even after the participants came out of trance.

The average score for the participants in the test group before being taught the NLP dissociation technique was 7.72. The reason why this score was high was probably because the participants were told to associate into the memory first and give a score for the intensity of the emotions. Subsequently, they were taught the dissociative technique. The average score in terms of intensity of the emotions after doing the dissociative technique was 3.25. T-tests showed that the differences were significant at the 0.01 level.

In relation to TLT, the average score of the participants for anger before being taught the technique was 6. The average score after was 1.28. T-tests showed that the differences were significant at the 0.01 level. Twenty five out of the thirty two participants managed to completely remove all of their anger from their past within twenty minutes – some were able to do so in less than ten minutes. Seven of the participants were not able to remove anger entirely from their past in the TLT group induction, although for all of them, the reduction was significant.

In relation to TLT, the average score of the participants for sadness before being taught the technique was 6.5. The average score after was 1.72. T-tests showed that the differences were significant at the 0.01 level. Twenty three out of the thirty two participants managed to completely remove all of their sadness from their past in the twenty minute process – some were able to do so in less than ten minutes. However, the remaining nine participants were not able to remove sadness entirely from their past in the TLT group induction, although, for all of them, the reduction was significant.

Comparing the different techniques, it can be seen that the average score of the participants after the procedure, were lower for TLT compared with hypnosis and NLP. In fact James and Woodsmall (1988) prescribes that in TLT, negative emotions are to be completely removed from the past. As mentioned earlier, many of the participants were able to remove their anger and sadness completely from the past. For the rest, they were not able to do so. A follow-up group interview was done on these people and the common reason cited was that they preferred a one-on-one session rather than a group induction and that there is one major event that they are not able to resolve.

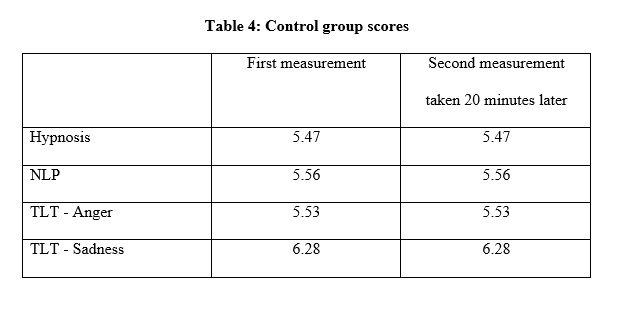

As expected, no significant changes in the scores of the control group were recorded. The average scores for the control group were as follows:

CONCLUSION

This study compared the relative effectiveness of hypnosis with techniques in two other separate but related fields – TLT and NLP. The sample consisted of 32 individuals in the test groups and 32 individuals in the control group. Measurements were taken before and after each of the procedure. The absence of changes in the control group in this study and the fact that there were significant reduction in stress levels and intensity of negative emotions in the test groups suggest that it is the techniques in hypnosis, TLT and NLP that are effective and are responsible for these changes.

However, some finer distinctions can be made here. For instance, hypnosis can be useful to get people to relax their mind and body. On the other hand, TLT is effective in removing specific negative emotions attached to all memories from the past, thus reducing or eliminating stress caused by these memories. The NLP dissociative technique is useful to take the “sting” or stress caused by painful memories from the past simply by changing the submodalities or the characteristics of the mental picture. Thus, although each of these techniques can be used to reduce stress generally, the way in which each of these techniques operate is different. Therefore, the practical implication to practicing hypnotherapists is that other techniques such as TLT and NLP can be employed along with hypnosis. Consequently, TLT and NLP should be viewed as complimentary rather than competing models with hypnosis.

Another interesting issue raised in this research is that some participants have reported preference for one-to-one sessions rather than group sessions. This was certainly true for TLT and hypnosis. Some participants commented that both processes took too long and their mind wandered. Others said that they wanted to take a longer time. Thus, the group sessions could not accommodate the different preferences of individuals. Actually, one of the participants who was not able to remove sadness at all during the procedure was subsequently able to remove them entirely when she signed up for the practitioner certification course and repeated the procedure, but on a one-to-one basis.

The limitation of this study is the lack of randomization of the test groups – most of them were self-selected as most of them chose to attend the seminar wherein the research was conducted. They were probably the most hypnotizable. However, 10 out of 32 of the participants in the test group (i.e. roughly one third) were not self-selected as they were directed by their superior to attend. Perhaps future research can compare the scores of those who were self-selected and those who were directed by their superiors to attend the seminar. Another limitation is that this study is cross-sectional, and there is no way of knowing whether the reductions in the levels of stress and negative emotions were permanent or temporary. Future research should take the form of a longitudinal study. Measurements can be taken in one, three, six months, and one year into the future. Also, groups that have taken refresher courses conducted by the researcher can also be compared with groups that have not. Also test groups consisting of people from different countries and cultures all over the world can be compared. In fact, this is the next research project contemplated by the researcher.

REFERENCES

Abramowitz, E.G., Barak, Y., Ben-Avi, I. and Knobler, H.Y. (2008). “Hypnotherapy in the treatment of Chronic Combat-Related PTSD Patients suffering from Insomnia: A Randomized, Zolpidem-Controlled clinical trial.” International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 56, 3, 270-280.

Alladin, A. and Alibhai, A. (2007). Cognitive Hypnotherapy for Depression: An Empirical Investigation. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55, 2, 147-166.

Anbar, R.D. and Zoughbi, G.G. (2008). Relationship of headache-associated stressors and hypnosis therapy outcome in children: A retrospective chart review. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 50, 4, 335-341.

Andreas, S. and Faulkner, C. (1994). NLP – The New Technology of Achievement. William Morrow, New York, NY.

Appel, P. (1983). Matching representational systems and interpersonal attraction (Doctoral Dissertation, United States International University, 1983). Dissertation Abstracts International, 43, 3021B, (University Microfilms No. 83-018, 35).

Astin, J.A. (2004) Mind-Body Therapies for the Management of Pain. Clinical Journal of Pain, 20, 1, 27-32.

Bandler, R. and Grinder, J. (1979). Frogs into princes: Neuro-Linguistic programming. Moab, UT: Real People Press.

Blanchard, E.B., Andrasik, F., and Ahles, T.A. (1980). Migraine and tension headache: A meta-analytic review. Behaviour therapy, 11, 5, 613-631.

Brockman, W. (1981). Empathy revisited: The effect of representational system matching on certain counselling process and outcome variables (Doctoral dissertation, College of William and Mary, 1980). Dissertation Abstracts International, 41, 3421A. University Microfilms No. 81-035, 91).

Bryant, R.A. and Fearns, F. (2007). Taking the feeling out of emotional memories: A study of Hypnotic Emotional Numbing: A Brief Communication. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55, 4, 426-434.

Carter, C. (2005). The use of hypnosis in the treatment of PTSD. Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 33, 1, 82-92.

Cody, S.G. (1983). The stability and impact of the primary representational system in Neurolinguistic Programming: A critical examination (Doctoral dissertation, University of Connecticut, 1983). Dissertation Abstracts International, 44, 1232B. (University microfilms No. 83-191, 87).

Cooper, C.L. and Locke, E. (2000). Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Linking Theory with Practice, Blackwell Business, Oxford.

Dilts, R., Grinder, J., Bandler, R., Cameron-Bandler, L. and DeLozier, J. (1980). Neuro-Linguistic Programming (Vol.1). Cupertino,CA: Meta Publications.

Dorn, F. (1983). The effects of counsellor-client predicate use in counsellor attractiveness. American Mental Health Counselor’s Association Journal, 5, 22-30.

Dowd, E., & Hingst, A. (1983). Matching therapists’ predicates: An in vivo test of effectiveness. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 57, 207-210.

Dowd, E., & Pety, J. (1982). Effect of counsellor predicate matching on perceived social influence and client satisfaction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 29, 206-209.

Ehrmantraut, J.E. (1983). A comparison of the therapeutic relationship of counselling students trained in neurolinguistic programming vs students trained in the Carkuff model (Doctoral dissertation Abstracts International, 44, 3191B. (University Microfilms No. 83-284, 91).

Einspruch, E.L. and Forman, B.D. (1985). Observations concerning research literature on Neuro Linguistic Programming. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 32, 4, 589-596.

Elkins, G., Jensen, M. and Patterson, D. (2007). Hypnotherapy for the Management of Chronic Pain. (2007). International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55, 4, 275-287.

Elkins, G., White, J., Patel, P., Marcus, J., Perfect, M.M. and Montgomery,G.H. (2006). Hypnosis to manage anxiety and Pain associated with Colonoscopy for Colorectal-Cancer Screening: Case Studies and Possible Benefits. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55, 4, 416-431.

Ellickson, J. (1983). Representational systems and eye movements in an interview. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30, 339-345.

Falzett, W. (1981). Matched versus unmatched primary representational systems and their relationship to perceived trustworthiness in a counselling analog. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28, 305-308.

Gay, M.C. (2007). Effectiveness of Hypnosis in reducing mild essential hypertension: a 1-year follow-up. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55, 2, 67-83.

Gilboa, S., Shirom, A. Fried, Y. & Cooper, C. (2008). A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology, 61, 2, 227-272.

Green, M. (1981). Trust as affected by representational system predicates (Doctoral dissertation, Ball State University, 1979). Dissertation Abstracts International, 41, 3159B-3160B. (University Microfilms No. 81-046, 51).

Greenberg, J. and Baron, R.A. (2000). Behaviour in Organizations. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Grinder, J. and Bandler, R. (1981). Trance-formations. Moab, UT: Real People Press.

Gruzelier, J., Smith, F., Nagy, A., and Henderson, D. (2001). Cellular and humoral immunity, mood and exam stress: The influence of self-hypnosis and personality predictors. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 42, 55-71.

Hammer, A. (1983). Matching perceptual predicates: Effect on perceived empathy in a counselling analog. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30, 172-179.

Hammond, D. C. (2007) Review of efficacy of clinical hypnosis with headaches and migraines. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55, 2, 207-219.

James, T. and Woodsmall, W (1988). Time Line Therapy and the Basis of Personality. Meta Publications, CA.

Jensen , M.P., Barber, J., Hanley, M.A., Engel, J.M., Romano, J.M., Cardenas, D.D., Kraft, G.H., Hoffman, A.J., Patterson, D.R. (2008). Long-Term outcome of Hypnotic Analgesia treatment for chronic pain in persons with disabilities. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 56, 2, 156-169.

Keefer, L. and Keshavarzian, A. (2007). Feasibility and Acceptability of gut directed hypnosis on Inflamatory Bowel Disease: A brief communication. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 55, 4, 457-466.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K., Marucha, P.T., Atkinson, C. and Glaser, R. (2001). Hypnosis as a modulator of cellular immune dysregulation during acute stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 674-682.

Kirsch, I., Guy, M. and Guy, S. (1995). Hypnosis as an adjunct to cognitive-behavioural psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 214-220.

Manzer, J. (2003). Medical Post, 39, 15, 18.

Neuman, P. (2005). The use of hypnosis in modifying immune system response. Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 33, 2, 140-159.

Paoli, P. and Merllie, D. (2001). Third European Survey on Working Conditions, 2000. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg.

Paxton, L. (1981). Representational systems and client perception of the counselling relationship (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University, 1980). Dissertation Abstracts International, 41, 3888A. (University Microfilms No. 81-059, 41).

Shakibaei, F., Harandi, A.A., Gholamrezaei, A, Samoei, R. and Salehi, P. (2008). Hypnotherapy in management of pain and reexperiencing trauma in burn patients. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 56, 2, 185-197.

Sharpley, C. (1984). Predicate matching in NLP: A review of research on the preferred representational system. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31, 238-248.

Smith, M (2003). Medical Post, 39, 10, 55.

Thomson, J. E., Courtney, L. and Dickson, D. (2002). The effect of neurolinguistic programming on organisational and individual performance: a case study. Journal of European Industrial Training, 26, 6, 292-298.

Treven, S. & Potocan, Vojko (2005). Training programmes for stress management in small businesses. Education and Training, 47, 8/9, 640-652.

VandeVusse, L., Irland, J., Berner, M.A., Fuller, S. and Adams D. (2007). Hypnosis for childbirth: A retrospective comparative analysis of outcomes in one obstetrician’s practice. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 50, 2, 109-119.

Willemsen, R. and Vanderlinden, J. (2008). Hypnotic Approaches for Allopecia Areata (2008). International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 56, 3, 318-333.

So, Does NLP Work? YES!

So, when your friends ask you, “Does NLP really work?”, you can send them to this article, and also to this one.